New science in the wetlands - Water ecologist Mennobart van Eerden has been doing pioneering research in the IJsselmeer region for over 50 years

It was in the early 1970s that Mennobart van Eerden, from Groningen, first visited the recently drained Flevopolder. He has been devoted to the wetlands and waterbirds ever since. He studied biology and worked for 42 years as a water system ecologist for the Department of Public Works. Even after retirement, he is still active as a researcher in what is now called National Park Nieuw Land. "I like to show that all these areas really belong together.

Two years after reclamation, southern Flevoland was still a vast wilderness that attracted many harriers, rough-legged buzzards, short-eared owls and geese. Even on the young Mennobart - precisely because of this bird wealth - the area had an enormous attraction. A few times a year, his parents brought him from Groningen to Harderwijk to walk the approximately 20-kilometer Knardijk to Lelystad. 'That pioneering phase was really very special. It was still a forbidden area because you could sink in that wet and soft soil. But from the dike you could already see how quickly nature adapted. Other plants appeared, saltwater fish made way for freshwater fish, and all kinds of bird species migrated here in thousands. I thought: what is happening here? How is that possible? That fascinated me enormously.

“ ‘A few centimetres difference in depth everything that determines which plant is there.’ ”

PhD

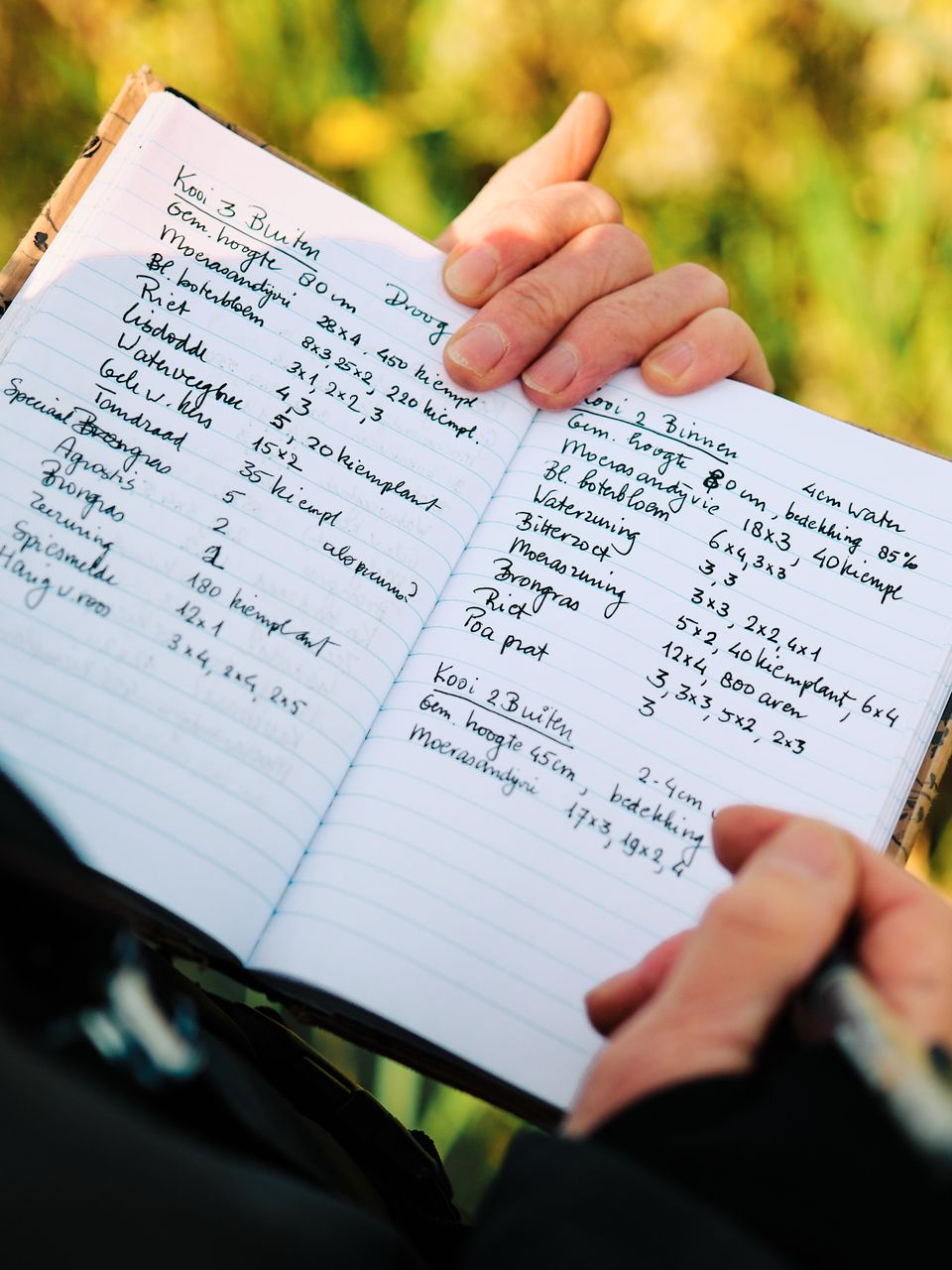

As a biology student, Mennobart used his fascination for a doctoral research project in the Lauwersmeer, in which he really started measuring and quantifying what was happening in the polder. That had never before been done in Europe at such a level of detail. 'You look at the density of species down to the smallest plants and you map out which seeds are in the droppings of water birds. In this way you can do sums and make connections between food richness and certain bird species. And more importantly, show how that develops over the years. Ultimately, this study contributed to my being asked to work for the National Service for the IJsselmeerpolders a few years later. So that was the same Government Service with whom I had once illegally walked through their territory! Later that became Rijkswaterstaat, of course, but I have always continued to work there.'

Impoldering Markermeer

The assignment Mennobart started in 1979 was to investigate the consequences of a possible impoldering of the Markermeer for water birds. In doing so, he found himself the only aquatic biologist in a motley crew of agricultural engineers, geologists and marine archaeologists who had little affinity for wetlands. 'These were all polder people who looked at the lake with a very different interest than I did. After three years of research, sometimes literally going into the deep end to watch diving ducks chase mussels and fish, my conclusion was that reclamation would mean the end of the rich bird life in this area. I won't claim that thanks to my report the reclamation didn't happen, but it undoubtedly played a role. More important was probably the reduced need for large-scale agriculture that the future Markerwaard would accommodate.

Hand on tap

In subsequent years, Mennobart helped shape the Oostvaardersplassen and cyclical water level management in the wetlands. He also set up a system of monthly bird counts from the air, which has now provided over 40 years of data on the bird population in the IJsselmeer region. 'From the knowledge and experience I had built up in the meantime, I knew that wetlands benefit from good dynamics in the water level. That was not there at the time, so we saw that the natural value of the marsh was declining and counted fewer and fewer herons, spoonbills, ducks and geese. Then we first tried to keep the water level high in the winter and low in the summer, as nature always does. That turned out to be insufficient for large-scale restoration of the marsh in the Oostvaardersplassen. For the open waters of the Markermeer and the IJsselmeer - from the point of view of agriculture and water safety - we even instituted a reversed water level regime, with a level 20 centimeters lower in winter than in summer. After all, the farmer wants to be able to drain in the winter and collect water in the increasingly dry summers. And because all these areas are interconnected, this in turn affects the water level in Marker Wadden and the ecosystem that depends on it. Our research is going to provide more insight into this, but what we already know is that a few centimeters difference in depth is all determining which bird can walk there or which plant is there.

Swamp reset

The Oostvaardersplassen will be partially drained by 2022 for the second time in its existence. With this so-called reset, which lasted four years last time (1987-1991), biodiversity will get another boost. Mennobart: "The permanently high water made the area especially attractive to geese who feasted on young reeds. And underwater carp in particular ate the mosquito larvae, which were therefore not available to the waders. By draining the area again for a few years now, it will be rejuvenated and the reeds will be able to expand again and take firm roots so that they will be able to withstand the water for years to come. At the same time, this is a nice experiment to see how the low water level in Oostvaardersplassen affects the flora and fauna, both here and in other areas, such as Marker Wadden and Trintelzand. Using new technology, such as transmitters, thermal imaging and motion cameras, we can see where teals and other waterfowl are and how they benefit from the seeds of the pioneer plants. That is the research I am currently engaged in, together with my wife who is also a biologist. Very nice to be able to do that together in this beautiful area.'